Customer Lifetime Value: Why Acquisition Still Matters More Than Ever

AI may help predict who stays, but growth still depends on who arrives. The future of CLV is about striking a balance between penetration and retention not choosing between them.

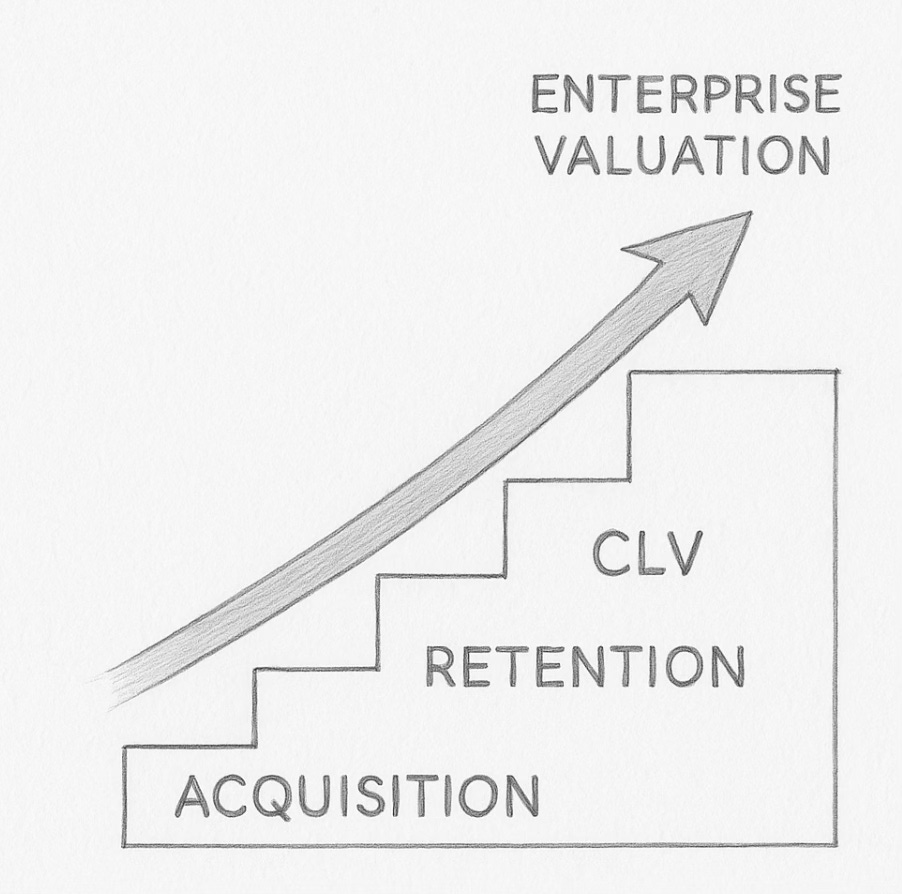

It still amazes me that when discussing customer lifetime value, there is an assumption that we are only considering customer loyalty, rather than a broader view of value, including acquisition, retention, and cash generation. This misstep simplifies what is a powerful valuation metric that should help define the enterprise value.

For years, marketers have been told to “focus on loyalty.” The story goes that if you can hold onto your customers for longer, everything else will take care of itself. It’s a comforting idea, but, as Byron Sharp has shown, it’s mostly wrong.

Brands grow not because they create a small army of loyalists, but because they reach more light buyers: the people who buy occasionally, forget you exist, and come back months later when reminded. Penetration, not retention, explains the majority of brand growth.

That doesn’t make loyalty meaningless. It means loyalty is *an outcome of reach and relevance*. You can’t retain customers you never acquired.

The myth of “lifetime” loyalty

The trouble with how Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) is typically discussed is that it sounds like a loyalty score, a measure of how long someone will remain loyal to a company. In reality, CLV isn’t about affection; it’s about economics

.

> CLV = (Revenue × Tenure) – Cost to Acquire – Cost to Serve.

Those last two variables, acquisition and service costs, decide whether a company is creating or destroying value. Every business can make customers loyal if it’s prepared to invest in them infinitely. The art lies in *reducing the cost per customer while maintaining reach*.

When you strip away the buzzwords, CLV is a measure of *marketing efficiency*. It’s the reconciliation between growth and profitability; the bridge between the CFO’s spreadsheet and the CMO’s ambition.

Acquisition is the engine; CLV is the gauge.

Sharp’s data show that brand penetration and market share are closely correlated. Brands with larger customer bases tend to have more repeat buyers. The implication is clear: acquisition drives retention, not the other way around.

But CLV adds a crucial dimension. It forces us to ask: *What does each new customer cost, and what are they worth over time?*

In the era of cheap digital reach, we stopped asking that question. Acquisition costs soared as competition and privacy restrictions made targeting harder. CLV brings discipline back into growth.

AI and advanced analytics are accelerating that shift. They enable marketers to model real-time value per segment, understand which acquisition channels drive the most profitable customers, and adjust spending dynamically. Acquisition hasn’t become less important—it’s simply becoming more intelligent.

AI and the new economics of value

AI is changing both sides of the CLV equation.

1. Smarter acquisition. Machine-learning models identify which audiences are most likely to convert and stay. That means fewer wasted impressions, lower CAC, and higher value per customer.

2. Richer retention. Predictive personalisation; AI-driven recommendations, dynamic pricing, proactive service extends tenure and increases frequency.

In effect, AI is transforming CLV from a historical measure into a forward-looking system of record. Salesforce, Oracle, and Shopify are all building platforms that use CLV predictions to guide real-time budget allocation.

The risk is that this becomes another arms race: vast investment in AI infrastructure chasing predictive accuracy, without addressing the fundamentals of value creation. Data can tell you who to target; it can’t tell you why they should care.

The Byron Sharp correction

Sharp’s work is the necessary antidote to the current fashion for over-personalisation. His central idea—that mental and physical availability trump micro-segmentation—remains the foundation of modern marketing science.

AI doesn’t replace that; it refines it. The future isn’t hyper-narrow targeting, but efficient broad reach: reaching as many potential buyers as possible, more cheaply and more meaningfully.

CLV, properly used, is how we test whether our reach strategy is sustainable. When acquisition efficiency improves, CAC falls relative to value created, and CLV rises. When we over-invest in narrow retention schemes or expensive tech stacks that don’t expand the customer base, CLV falls.

In other words, CLV keeps the system honest.

Value as an organising principle

In From Paint to Profit, I argue that value is the only common language that unites marketing, finance, and operations. CLV is its most practical dialect.

It forces cross-functional alignment:

Marketing focuses on the quality of acquisition.

The product ensures that customers experience value worth paying for again.

Finance ensures cost discipline and sustainable margins.

Leadership links all three to shareholder value through NPV, not quarterly ROI.

It’s the difference between buying growth and building it.

Three lessons for the next era of growth

1. Reach still rules. Penetration drives growth; loyalty follows scale. Keep investing in reach but measure it through value, not vanity.

2. Efficiency decides survival. CLV is the compass that tells you whether each new customer adds or subtracts from enterprise value.

3. AI is the amplifier, not the strategy. Use it to reduce friction and improve prediction, but remember: algorithms predict behaviour; they don’t create preference.

The future of CLV

The next decade won’t belong to the brands with the lowest acquisition costs or the highest loyalty scores—it will belong to those that integrate both. The winners will treat CLV not as a marketing metric, but as a management philosophy—a way to connect customer experience, financial performance, and corporate purpose into a single measure of value.

Growth still starts with acquisition. But CLV ensures every new customer is worth acquiring again.